Market pricing, the compromises we make and our insatiable quest for a great deal (aka value)

By John Jarvis

Through the years I have used a simple graph to explain a concept about market pricing and value. At some point I started calling it the “Jarvis Value Model,” and whenever I draw it on a whiteboard I always add a copyright symbol, you know, just in case.

As an economics major at the University of California, Santa Barbara, I learned that economics, in the end, is a social science—it studies human behavior and decision-making. I also learned the best concepts are basic concepts which can be represented in a simple graph. Supply and demand. Diminishing marginal utility. I think we all understand these concepts—the first donut tastes great, the 13th donut not so much. In particular, I remember the Modigliani Life-Cycle Hypothesis, which describes how we accumulate wealth over our lifetime, up to a point, after which we draw down our resources until our demise. Don’t get me wrong, Franco Modigliani was a very smart man. But I was struck by the simplicity of this concept, and the incongruous fame it seemed to have brought upon Mr. Modigliani. He’s not quite rock star status—I don’t think he was ever asked for his autograph—but this simple concept (among others) brought him considerable fame and fortune.

So here is my contribution to the economic field, a tip of the hat to my UCSB Econ Professors, and my modest attempt at fame and fortune alongside the great econ minds of our time.

Part One−The Concept

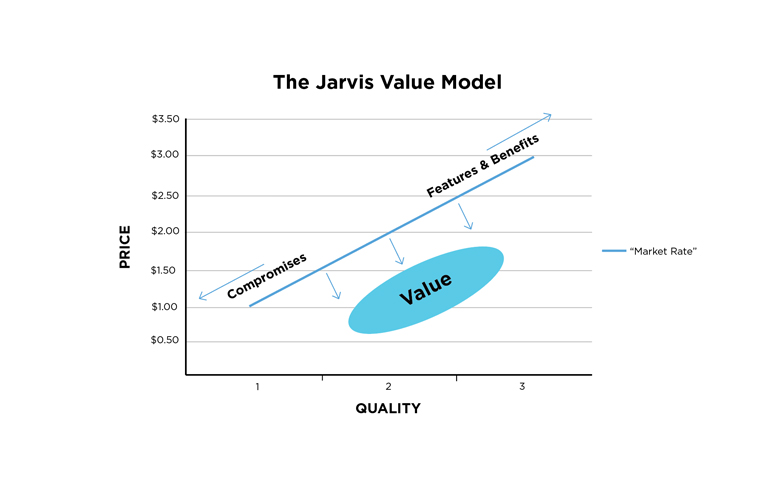

Everybody wants to get a great deal. It is human nature to not want to overpay for something and get a bad deal. We even have a tendency to brag about the great deals that we got with a sense of heartfelt pride. But what we really want is to pay less for something than it is worth, and to thereby create and enjoy instantaneous “value.” We go out of our way to pay less or to get more. And the key here is, just how far did we go out of our way? In other words, what compromises did we make in the interest of getting a “great deal?” I contend that in efficient markets items rarely sell for less than they are worth. As an econ major, I learned about market efficiency, and the tendency of efficient markets to quash windfall profits (with competition) and to stabilize prices around some “market” or “value” definition. There is no free lunch. But if almost everything is selling for approximately what it is worth, then how are we all bragging that we got such great deals?

I suggest that we all allow ourselves a little harmless self-deception in order to feel better about the “deals” that we get. And that this self-deception comes in the form of the compromises we make, for example, in pursuit of a lower price.

“In every instance, price is driven by circumstance, information and leverage.”

While shopping for a new car lease, we might sign up for a five-year lease (instead of three), or convince ourselves that we won’t drive more than 10,000 miles a year (when 12,000 is more realistic), or increase the amount that we pay up front so that our monthly recurring charge will be lower. There are examples like this in every facet of our lives as consumers. We shop at Costco, where we pay an annual fee for membership and where we sometimes buy more of certain things than we actually need. Maybe we store these bulk supplies and use them eventually, and maybe we don’t because they go bad or get lost or broken. We are willing to take these risks of bulk inventory storage because the lower price feels so good. Or we shop at Nordstrom Rack, because we are getting the same clothes that were at Nordstrom at a substantial discount to their original retail price. But they aren’t the same clothes, really. These are the clothes that didn’t sell, they have been on the rack a little too long, maybe past their season. There may be some good stuff at Nordstrom Rack, but you have to look a little harder, stand in line a little longer and ultimately settle for something less than the original retail Nordstrom experience. Is it worth it? Sure, go for it. And recognize that we are making these compromises in the interest of price.

There is no judgment intended here. What I am advocating is simply that we all recognize the compromises we make in pursuit of a lower price. Whether we pay top dollar for the original retail experience, or the discounted price for a certified, pre-owned version of the original, we are merely moving up or down a line that represents “market rate” and we are still paying some variant of the market price.

And here is the good part—all that elusive “value” we seek, the free lunch, is sometimes attainable, and it resides “below the line.”

Part Two–Finding “Value” Below the Line

I negotiate real estate transactions for a living. As a corporate real estate broker specializing in tenant and buyer representation, I operate exclusively on the acquiring side of the transaction. After 30 years in this business, here is the secret I have learned—commercial real estate transactions do not always settle at the “Market Rate” or “Fair Market Value.” The stock market is an efficient marketplace, where millions of buyers and sellers interact every second, setting and re-setting the market price for each share of stock. Commercial real estate is a very different game. Consider, every piece of real estate is unique and every seller or landlord faces a different set of motivations and challenges, which change over time. Likewise, every buyer or tenant is unique, what they need, when and for how long, and, of course, this too can change in an instant. I have seen far too many crazy deals, “outliers” and pricing anomalies, to believe in market efficiency in commercial real estate. I am often surprised by just how far a landlord is willing to stretch for a deal that they really want, or what a seller will ultimately accept when, for example, their board of directors finally decides to cut and run on a particular asset. When you live and work on the acquisition side of commercial real estate, it is risky and naïve to trust in the fair market value approach to real estate pricing. In every instance, price is driven by circumstance, information and leverage.

There will be those who resist this notion, those who believe in and rely upon fair market value appraisals, sale comparables and lease comparables (aka recently closed transactions). And they have a point, generally. These historical valuation metrics are one way to assess price and value in general, but not specifically. Furthermore, they are historical by definition. They look back in time to evaluate what certain people were willing to pay yesterday, which has only a limited application in determining what different people will be willing to pay today or tomorrow. Think about it—a lease or sale comparable that is six months old is reflecting terms that were agreed to perhaps six months before that. A particular buyer/tenant came to agreement with a particular seller/landlord for a particular parcel of real estate over a year ago! Talk about living in the past.

So here is my point. Value is found below the line. At Hughes Marino, we love to play below the line. Commercial real estate is an inefficient marketplace, and in any part of the market cycle there are always value opportunities. We want companies to recognize when they are making compromises in pursuit of price, and we want to educate our clients on the difference between low price and great value. Below the line is the sandbox where we play.

OK, so maybe you’ll never see the Jarvis Value Model in an econ textbook. But it is definitely in the Hughes Marino playbook. Let me know if you want a signed copy.

John Jarvis is an executive vice president of Hughes Marino, a global corporate real estate advisory firm that specializes in representing tenants and buyers. Contact John at 1-844-662-6635 or john@hughesmarino.com to learn more.